THE FLOCK

“Hey, Grace, didja see the flyers all over the place about Mary Taube gone missing?”

Duke flipped the Mountain Valley Feeds cap around to the back of his head and adjusted

his belt below his belly before straddling the stool at the corner of the counter by the

coffee pot. He’d stopped removing the hat as the bald space on the back of his had started

spreading like an egg on a cold pan. A guy has some pride after all.

“Yeah, “ Grace replied, “Marty said him and the other guys over’t the sheriffs’re headed

up to the park right now to check for her there. She goes out on the dock on the south side

of the lake to draw.” Grace slid the extra bowl of creamers by his mug and poured the

acrid coffee in his cup.

Nodding, “Ayup. That south side stays sunny even this time of year. She’s always up there

drawin’. I’ve given her a ride up there myself lotsa times. I hope some creep didn’t nab

her,” Duke replied, gulping coffee to wash the antacid tablet down his throat.

Grace wiped the counter, then leaned close to Duke, saying, “Nobody better touch a hair

on her head, that’s what I say. You know what that kid did? When Marty got killed over

there in Afghanistan, and they sent his body back, she dug up some ol’ picture from when

they were in high school, and drew him, like he was back then, alive and smiling. She

gave it to me at the memorial service. I framed it and have it hanging by my bed. I look

at it every night.”

“ Aw, Grace. That was real tough. I’m glad you got that picture to look at. Ayup, she’s a

real nice girl. Laughs at my lame jokes on the way up to the lake. I never did like to see

her walking up there by herself. Christ, why didn’t her dad come around after Holly

passed? Jackass. Someone shoulda been in that house with her.”

“ I dunno. Shame. I heard he’s holed up in Juneau with some Eskimo gal.”

The walls rattled as Schmidt lumbered through the café door.

“Mornin’, all. Grace, gimme some of that battery acid you got in that coffee pot. Duke,

man, you look fatter every time I see you. Make me look svelte,” Schmidt boomed as he

hung his canvas jacket on the third hook and heaved himself onto the stool one over from

Duke. The big men always left a space between them, for a midget with no arms, they

joked.

The comforting smells of grease and bacon and syrup hung in the airspace in the singlewide

diner as the griddle in the back fired up and regulars ordered their breakfast combos.

The Olympia clock ticked, but the second hand had caught on 2, so other than its

comforting heartbeat, it was useless. Grace had never put in speakers, preferring instead,

the regular waves of conversation from the murmurs of breakfast, to the clatter at lunch,

and the laughter of the folks after work. Everybody in the mountain community checked

in at Grace’s place at least once a week.

That morning the hum was louder, higher-pitched, circling the room quickly without

ebbing. About the young woman missing from their midst. Mary belonged to them. The

sheriff had checked her house when old Mrs. T called them saying Mary hadn’t shown up

to do the ironing, like she always did on Mondays. Mrs. T called at least once a week

about something, but the sheriff went over to check on the girl anyway. Things were

slower in September after the summer tourists and their drunken family reunions were

gone.

The doorbell at the Taube house still didn’t work, so he knocked. He didn’t use the brass

knocker either. He never did, feeling that clacking on those things was kind of

aggressive. Nobody locked their doors in Sweetholm, so after knocking and calling out

hello with no reply, he let himself in. At first glance, there was no sign of anything amiss.

His eyes took notes:

• Rubber boots, sneakers, hiking boots, and slippers lined up evenly under the

jackets.

• The worn black and white linoleum tiles swept clean.

• One set of dinner dishes, washed and arranged in the drying rack beside the sink.

• A Safeway sack stuffed with recyclables.

• The kitchen table strewn with white sheets of paper that fluttered in the breeze

blowing through the open window.

Mary drew people and birds. Everybody knew that. Phil Braun looked down at the pale

graphite faces and wings, and remembered when his own daughter Lisa had been in art

class with Mary. What was that good looking gal’s name, the one who came to the school

once a week to teach art? Hell, his memory was shot. It had been three years since the

high school offered anything special anyway. Times were tough, he understood that, but

the abandonment by the state annoyed him nonetheless.

The bungalow’s front room looked just like when Mary’s mom, Holly, had lived there,

except that Mary had tacked up her drawings of Canada geese on the green wall.

Upstairs, the first bedroom door was shut. He peered inside. Holly’s room. Stepping in

the darkened space, he smelled lavender. When he twisted the wand on the blinds, sunlit

stripes zigzagged across the room. Little silver animals lined up on the dresser, and the

white bedspread fringe hung quietly. Holly had died two years ago. Well, what else

would Mary do with that stuff, besides leave it in here, he thought to himself.

Nothing, no body, or anything unusual in the bathroom. The cup next to the sink held a

toothbrush and a half-squeezed toothpaste paste with no top on it. The claw foot tub

seemed clean enough when he drew the shower curtain aside.

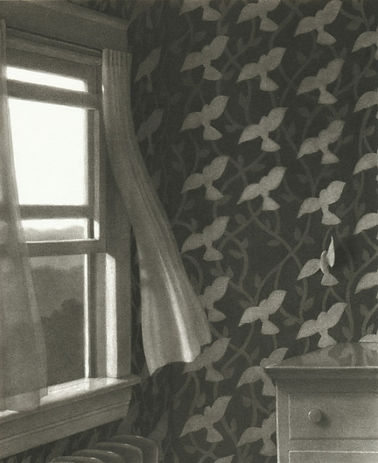

The door to the second bedroom was ajar, the sunshine wafting in with the Indian

summer smell of dried grass. He stepped in the room. The twin bed had been made with

a crochet cover laying on over a pale yellow blanket. He had one too; there were a few

years in the fifties when all the ladies made them. White woodwork outlined the dove

grey wallpaper with the vine pattern.

He opened the drawers of the chest one by one,

pushing aside the jeans and sweaters. The sheriff hated this part, the snooping. Up here,

there just weren’t secrets. The white cotton underwear was stacked next to a couple beige

bras, and a few rolled up pair of knee socks. He closed the drawer.

When the sheriff got back to the office, Marty asked if he’d found anything. “Nope, he

sighed. Sheriff Braun filled out the first missing person report of his twenty-four years on

the job.

High Risk Missing Person Report:

Missing from Sweetholm, WA

Mary Elizabeth Taube , ###-##-7557

Female, aged 18

Caucasian

Hair: Light brown Eyes: Brown

Height: 5’5” Weight: 150

Distinguishing Features and Marks: Wide forehead, small eyes. Slow speech.

Clothing: Jeans, Blue t shirt, grey down vest. Believed to be wearing brown oxford shoes

and knee socks.

Other: Carrying black sketchbook and red backpack

Last seen: Walking north on Sweetholm-High Valley Road, 1 pm. September 9.

Risk considerations: Taube is learning impaired and has no legal guardian.

The clucking and clinking at the diner had subsided. Everyone would scout around for

signs of Mary and return in the evening.

It was Duke. Duke saw the white sheets flutter up behind his truck as he rounded the

sharp curve in the road at the foot of the hill. They caught his eye in the rearview mirror

as he geared down to climb the last half mile up to the lake. He couldn’t pull off the road

‘til that gravel spot about a 600 feet further. Yanking up the parking brake, he pressed on

his hazard lights, and trudged back down the gravel to the spot where the white papers

had been.

Darn narrow shoulder, he thought. There wasn’t enough room for a body to

squeeze along. He’d have to put his back to the sharp cliff if a big car came along.

Spring water perpetually seeped down the basalt face on his left. He shielded his face

from the splash. Rounding the bend, the gap between him and the cliff opened up.

Rivulets splashed now, bouncing mist off his face and then falling to the chasm below.

The river tumbled from the lake above and grew swifter as it carved its way through the

spring-fed cliffs.

Duke spotted the black spine first. His stomach twisted. The covers lay nearby and then

the pages. Mostly they were in hanks, but a few single sheets lay scattered about the dark

gravel. He bent down, picking them up. There was a goose with an S shaped neck. He

recognized faces, smudged and misshapen from the mist, but there they were, Mrs. T

with her crazy hair, Jake Palmer, the grocer, resting his head in his large palm, and…his

own profile, staring ahead in his truck. Mary!

He stepped toward the edge, pressing his shins against the guardrail and focused his eyes

on the river below. He scanned the boulders, the grey silt of the glacial water, the piles of

tree trunks that crashed down in the spring runoff each year. Lodged in the debris, in the

only spot of sunshine to penetrate the ravine, he thought he saw an arm. No…dear God,

no. Yes. That was what it was. What he did not want to see. He groaned. Oh Lord. No.

Duke felt for his phone. Damn, he’d left it in the glove box. He trundled back up to the

truck. Panting and sweating, he flung open the door and reached for his phone. He dialed

Phil Braun’s number.

“Phil. Phil, it’s me, Duke. You gotta get here. I’m at the curve, the one below the park.

Phil, I found her. Mary’s dead, down in the river. Call Matt. Tell him to bring his tow.

We’re gonna need a lot of guys. She’s wedged down in there pretty good. OK, I’ll be

here.”

The sheriff and his guys got there fast, straight down from the park where they left a

stinking goose carcass for later disposal. Matt took a little longer to come up from town

with the tow. The guys who worked ski patrol in the winters were the fittest of the bunch,

so they rappelled down to the ravine. It took a lot of prying to dislodge the body from the

debris. With the winch from the tow, they were finally able to swing the last tree off to

the side, to free the girl from the icy water.

They strapped her into the canvas sling, and the tow hoisted her back up over the

guardrail. Duke hung his head down over the bluish grey face that unnaturally aligned

with the shoulders, the eyelids closed, the nose broken, no expression whatsoever. The

dark hole beneath the white jaw was only visible when they lifted the corpse from the

webbing, and her head fell to the side, undone from the neck.

Duke walked to his truck where he doubled over the wheel and wept.

Mary Taube’s funeral was held at the Sweetholm Presbyterian church, where Holly was

buried. They never did locate Mary’s dad, so they took a collection to pay for a casket for

Mary’s body and gathered there to pray for her soul. After the service, the flock headed to

Grace’s place for coffee and donuts which Grace provided free of charge. They talked so

low that day, they could hear the Olympia clock ticking.

The next morning was warm again, the kind of late September day when God gives you a

little sunshine before he draws the curtain of winter across the mountains. Already, the

rains had come in for a couple days to remind folks to put the lawn chairs and barbecues

in the garage. The rain and rust up here were relentless.

: : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Mary wiggled her toes in the foot of the knees socks. She wanted to be sure her toenails

didn’t catch on the loose threads inside. All clear, she eased each foot into its proper boot,

and snugged the laces up the grommets, the ones around her instep tight, and the rest

loose, ‘til everything felt just right, the way it did every morning.

Pulling the grey down vest off the hook, she slipped her arms in the holes, left first, then

right. She liked Mom’s old vest best because it kept her own heat in, but she could still

feel the first cool breezes of early fall coming through the seams. She wouldn’t need to

zip it today, she thought, looking out at the promising rays filtering through the leaves.

Like Jesus himself reaching down to kiss the top of her head.

Bending them back, she creased a few pages from the sketchbook, the

ones that were really finished. She tore each one out separately, so as not rip them.

Remembering she would need to buy more thumbtacks at Jake’s, she added

THUMBTACKS to her list on the back of an envelope by the phone. She would hang

them up later, when she got back. Sliding the sketchbook in her red backpack, she

gathered up the pencils on the kitchen table. Only the 5 B needed sharpening, so she took

it over to the sink and pulled the sharpener from the little bowl containing rubber bands,

paper clips and bread bag tags. This was the last 5B. She went through these the fastest

because they were soft, and she like them the best for beginning her sketches. She wrote

5B on the envelope.

With her salami sandwich and water bottle snugged in the pack, she closed the door and

walked towards the corner store on her way up to the lake. Mrs. Jake, Mary always called

her that, which made them both giggle, was standing behind the counter.

“Hi, Mrs. Jake. Got some cake?” Mary’s joke never got old for either of them.

Denise Palmer made it a point to be nice to the simple girl who stopped by to cash her

social security check and buy a few things. She always carried supplies for Mary, like art

pencils and sketchbooks, the same way she stocked those agila lures for Phil Braun and

his steelhead buddies. Denise’s inventory was particular to the needs of Sweetholm’s 642

residents. Denise liked living in a small town where people mattered and you took care of

each other.

“Mary, I don’t have cake to take to the lake!” She responded this way every day. And

both of them were happy with the exchange.

“Is there anything else you need today, Mary?” she asked the teenager whose mouth hung

open slightly. She wasn’t pretty, or little, nor did she have any endearing mannerisms, but

Mary was Denise’s favorite and most regular customer. Every midday, Mary showed up

with her her loose jaw. Sometimes she wanted to buy something, and sometimes she just

came in to ask her cake question.

“ I want to buy thumb tacks and a 5B pencil, Mrs. Jake.”

Denise stepped out from behind the counter and led Mary to the office supply section of

Aisle 2, next to the antifreeze and cat litter.

“Here they are, Mary. Here’s a little box of thumbtacks and one 5B pencil. Would you

like me to sharpen it for you?”

“Can I do it, Mrs. Jake? I want to use the sharpener.”

The two went back up front. Denise set the electric sharpener on the counter for Mary

who steadied it with her left hand, looked Denise in the eye, and guided her brand new

pencil into the whirring hole. Mission accomplished. Out came the pencil, sharp, and

entirely pleasing to Mary.

She paid $1.89 to Denise from her change purse which she then put back in the outer

pocket of her pack, along with the pencil and the thumbtacks, and zipped it up. She

pulled her arms through the straps and grinned at Denise, just as she had when she was

eight. She hadn’t changed.

Denise had tried to comfort the girl when her mother died, but hadn’t been able to locate

a tender spot that might cause the girl to release pent up grief.

“Will I have to cook my own dinner now?”

”Can I keep sleeping in my own bed?”

These were the kinds of questions that Mary had. Denise and her sister-in-law, Grace

Johnson, had spent a few weeks after Holly’s death teaching Mary how to boil water for

mac and cheese, how to fry hamburger, and how to nuke frozen veggies. She already

knew how to do laundry. They noted that she was fastidious about measuring detergent,

so they decided not to worry about a flood.

Grace had even spent that first month sleeping in Holly’s room, to keep Mary company,

and to ascertain just how capable Mary would be at taking care of herself. She found that

Mary’s life and routines were so well established and unvaried that Mary was capable of

living on her own. Still, she would never let Mary fall through the cracks. She would hold

the girl close. She had all kinds of room in her heart now…

“Thank you, Mrs. Jake. See you later,” said Mary in her learned, formal way.

Mary crossed the street in order to walk on the shoulder facing traffic. Mom told her.

Sheriff Braun told her. So, she knew. She knew she was to stay on this side of the road,

so she could see cars coming. She would stay out of their way. She would not get hurt.

Pay attention, Mom said, and she did. She started walking up the road to the lake.

Sometimes Duke would give her a ride when he was going up to the warehouse. Even if

he didn’t, it only took her twenty minutes to walk up to the dock on the lake.

The dock is where she liked to sit. The ranger was no longer at the ticket station after the

High Valley Lake sign. She walked by his little booth. Rodney went back down to Cle

Elum every fall, to be closer to his kids. Being a ranger was his retirement job, he had

told her. It paid for Christmas presents.

Her shoes ground into the hard pack, and she stayed in the middle of the road where last

spring’s run off had not left the washboard ribs as it had in the tire tracks. This year, the Forest

Service had made no repairs.

Rodney said he wasn’t even sure he would have a job next summer, and had hugged her hard

when he said goodbye two weeks ago. “ You keep drawing your birds, young lady. That

is your job here, and it is very important that you keep paying attention.” She thought

about that as she crossed the empty parking area and walked out on the planks. She took

her job seriously.

She inhaled before sitting down, the creosote rising off the wood in the afternoon sun.

The astringent fir smell surrounding the lake would wane soon, when the rains began, she

knew. She inhaled again. She sat down next to a piling where she could lean her back and

loosened the drawstring of the backpack. She pulled out the baggie with the salami

sandwich inside and her water bottle that Mrs. Haines from the high school had given her

last summer, an extra from the cheer squad fundraiser.

Biting into the whole grain bread, she looked across at the ridgeline to the east. The

serrated edges of the treetops tops quivered with the sun’s rays behind them. Just below,

all edges disappeared and the shadows grew black and she could see no outlines. Not

until her gaze dropped to the trees on the bottom third of the hillside did details begin to

emerge to the naked eye. She heard a car go past at the base of the hill. As it headed

further up, she saw the dust trail it left behind along the fire road.

Almost on cue, as she pulled out her pencils wrapped in a rubber band, she heard the

honking and squabbling. The Canada geese paddled towards her from the marsh grass a

little further on up the water’s edge. The cacophony preceded and conflicted with the

tight ranks of birds gliding towards her on the lake. She often wondered how God could endow

such beautiful creatures with such an imperfect voice.

The water behind each bird trailed in herringbone shimmers of sky and shadow, and the whole

squad moved in deft unison towards her. She opened up the black sketchbook, bending back

the spine, so that today’s blank page lay flat. Today she would work on Number One’s wife.

The birds did not invade the surface of the dock as Mary had never fed them. Gradually,

their announcements petered off, and some did figure eights off the front of the dock,

while others circled around the pilings, nibbling and tugging at the algae growing on the

ropes. Mary and the geese had no need communicate in any other way.

Exhaling, she stared at the one she thought might be Mrs. Number One. All these fowl

had white chin straps like bandages, underneath their black faces and above their black

necks. The tips of their tail feathers were the only other visible black spots on the birds

when they paddled in the water. Mary often started her drawing by defining the head and

making a mark where the tail feathers would be. The rest, in between, the breast and

back, called for a lot of subtle shading. It took a long time to build up those greys. She

knew because she used up a lot of 5B pencils on the middle bits.

She thought Mrs. Number One was a bully because she would open her beak wide and bray

at the other members of her clan. Bray, like a donkey is what Mary thought.

Mrs. Number One pulled her small black head back before she let the others know what

she thought of them. It made an S of her long dark neck, and as she released her brazen

honk, her neck would bend in the opposite direction, like an apostrophe. Punctuation

marks, thought Mary. Mrs. Number One did most of the talking, while the others shot

back occasionally and only when they were far enough from her to avoid being bitten.

The dominant female controlled the comings and goings and kept her position at the

center of the flotilla. Mary examined her closely. As she filled in the greys between the

punctuation marks, her pencil never lost its connection to the paper.

The first shot broke the connection and the rhythmic patterns on the water. The geese all

honked at once and began to lift and scatter, not a gracious gesture for the

large creatures. Right behind, the second shot hit Mary below her left ear. Her back

slipped off the piling and her head hung over the edge. The third shot penetrated the grey

feathers of Mrs. Number One’s breast and stopped at her heart before the goose could

heave herself from the water at the center of her flock. The honking of the dispersed

geese receded up the valley. The rippled Vs, purling on the water’s surface, sank into the blue.

Besides the whispering of Mary’s pages catching a breath of air as it passed over the

dock, nothing moved.

Dust followed the man’s truck as it descended the fire road towards the lake. The sound

diminished when it reached the tarmac, then resumed again as it wended its way up the

rutted road to the lake parking lot. He’d been up here once with the old man when he was

maybe ten, before he’d moved to Tukwila. It was good to hunt again, like he had with his

dad, before everything went to hell. The work at the assembly plant was steady, and he

was lucky to have it with his record and all. He hadn’t fucked up once. This was the first

break he’d taken in the two years since he’d been out.

He pulled out the tyvec IKEA bag from behind the passenger seat, and got out of the truck,

leaving the keys in the ignition and the door open. There was no one around, so he didn’t have to worry about the shotgun. He thought maybe he’d bagged a goose, and be right back with it in the bag. His rubber boots squeaked as he walked toward the dock. Heinhaled the sharp fir fragrance and wondered why he lived down below.

Then, as he stepped onto the dock, he saw the shoes, the legs, the backpack, and the open book. He stopped. His breathing stopped.His heart lurched and banged. Blood flushed into his head and stomach, and he stepped back. He was fixed in that place, faint headed with his heart pounding like a cop at a crack house door.

How long was it before he unlocked his knees? He fought back the urge to puke and

leaned forward as though, if he leaned, it would compel his feet to move. They did move,

separate from his brain. He stepped toward the person, a biggish girl, her head hanging

off the side of the deck, blood dripping from her neck. She looked dead. Was she? Oh,

shit, shit, shit!

It was all he could to touch her arm. It was cold, which made him flinch. He pulled her by

both arms to get her completely flat on the boards of the dock. She was definitely dead.

Like lightning striking, his head began to crackle with the possible outcomes to this total

clusterfuck. Every circuit rattled with scenarios, dead ends, desperate paths to escape.

Three strikes you’re out, dude. He looked up the valley, then, across the parking lot. This

was the end of the road; he could only drive back down the way he’d come up. He hadn’t

stopped in that town. Had anyone seen him? Oh, shit, shit, shit. The blood drained from

his face as he looked down at the girl, lifeless and bent. He thought fast.

He couldn’t leave her here. He had to get rid of her. Where? How? Go man, go. Don’t

stand here. Every minute you stand here, you’re closer to dead. He gagged as he bent

over and pulled the girl up to her feet, so that he could lift her over his shoulder. Fuck,

man! He faltered under her weight, and his knees buckled when he stepped off the dock

onto the gravel parking lot. The girl fell from his shoulders. He began to hyperventilate.

He pulled her up again by her arms, and did not look at her face. Do this, man. He

managed to heave her on his shoulder again, and weaved to the truck.

The beeping of the car key in the ignition registered as a sound from another world. How

long had he been away? He managed to set her shoulders onto the edge of the cab. When

he released her arms, her skull thumped on the metal bed. The hips had to be shoved, and

the shoes hit the bed of the truck next. One, two. What would he do?

He dry heaved right there. His head hot and his ears flushed, he stumbled back to the dock where he gathered the backpack, the IKEA bag and the black book. He kicked the pencil into the water. Peering over the edge, he saw the blood stain soaking into the old piling. There was nothing else. Mrs. Number One’s body had floated underneath the dock where he could not see it. It would rot.

After throwing the things in the back with the body, he pulled himself into the driver seat.

What, what, what… He turned the key in the ignition, shifted into reverse and pulled the

truck out of the parking lot. His load bumped as he navigated the gullies and washboard

surface on the narrow road to the gatehouse. He turned right and began down the road,

his eyes twitching. He wasn’t sure if he was breathing. He looked ahead only.

He could not go on, he thought.

Then, he saw the guardrail on the opposite side of theroad, above the river. Quick. Quick. Dude. Now. Veering across the road to it, he jumpedout, lowered the rear gate, and pulled the girl out by her legs.This time it was easier to get her over his shoulder, from this height. Then, he managed to rest her hips on the barrier and pushed hard on her feet to send her tumbling down the vertical face of the ravine. He could see that the body had reached the edge of the rushing water. The backpack and the IKEA bag remained in the bed.

He slammed the gate shut, got back in the cab, pulled into gear, and he did go on, down the county road.

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

The sheriff went over to Mary’s house to lock it up before it got turned over to a realtor to put

on the market. Maybe it would be a second home for someone from down below. He wiped down the clean dishes, just because, and set them in the cupboard. Unpinning the geese from the living room wall, he put the tacks in the dish by the sink. The geese went into a folder to take to the church. The stairs creaked as he moved upstairs.

He closed the door to Holly’s room, leaving the miniature silver animals lined up. The

executor would run the estate sale and the doodads would likely find a new home in

town.

The window was still open in Mary’s room, the voile curtains lisping in the breeze. He

stepped towards it, to shut it for the coming cold nights, when he felt the room shift. The

soft grey wallpaper with the vine pattern was now filled with birds, white birds, doves, lined

up, peacefully arranged within the white frames of the woodwork. What had caught his

eye to this change, was the motion of a wing settling into place. He felt it, but had not

seen it.

Then, his mind settled on a blank space in the pattern where a bird was missing.